FCRA “Concise Explanation” Standard: Ruling by Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

By Paul L. Scrom, Jr., Esq., Jules Halpern Associates LLC

To protect consumers’ privacy rights, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (“FCRA”) requires employers who conduct background checks on job applicants to provide a standalone, “clear and conspicuous” disclosure of their intention to obtain a consumer report, and the applicant must give their consent. The purpose of the disclosure statement is to provide job applicants with an easily digestible summary of their rights under the FCRA.

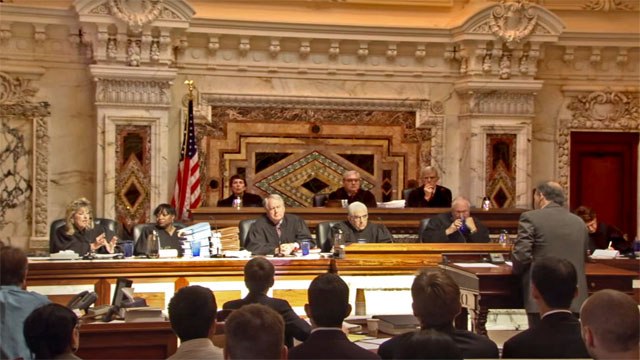

In a recent U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case, a job applicant challenged an employer’s FCRA disclosure statement, alleging that the form contained extraneous information and was therefore not a standalone document. After examining the disclosure form, the Ninth Circuit created a new standard that an employer’s background check disclosure form may contain a “concise explanation” of what the documents means.

What is the FCRA?

The FCRA is a federal law that regulates the collection, dissemination, and use of consumer information. The FCRA aims to promote the accuracy, fairness, and privacy of information in the files of consumer reporting agencies. Many employers use consumer reporting agencies to conduct background checks on job applicants.

“Clear and Conspicuous” Disclosure

The FCRA requires employers who utilize background checks to provide the job applicant with a “clear and conspicuous” disclosure that states the employer may obtain a consumer report for employment purposes. In addition, the applicant must give their written authorization for the consumer reporting agency to conduct the background check. The FCRA further states that the disclosure must be “in a document that consists solely of the disclosure.”

In a January 2019 case, the Ninth Circuit ruled that the FCRA prohibits any extraneous information from being included in the disclosure [Gilberg v. Cal. Check Cashing Stores, LLC, 913 F.3d 1169 (9th Cir. 2019)]. A recent Ninth Circuit case added some clarification as to what information may be included in a FCRA disclosure.

New “Concise Explanation” Standard

In Walker v. Fred Meyer, Inc., 953 F.3d 1082 (9th Cir. 2020), the plaintiff applied for a job at Fred Meyer’s supermarkets. As part of the application process, the plaintiff was provided with two forms related to a background check: a “Disclosure Regarding Consumer Reports and Investigative Consumer Reports” form and an “Authorization Regarding Consumer Reports and Investigative Consumer Reports.” The plaintiff completed both forms and returned them.

The plaintiff was hired as an associate, subject to the results of the background check. Several weeks later, the plaintiff received a “pre-adverse action notice” from the company that conducted the background check. The background screening company provided the plaintiff a copy of the consumer report, explained that the supermarket uses the report “in evaluating individuals for employment,” and notified him that he could dispute the accuracy of the report with the background screening company. Ultimately, the supermarket terminated the plaintiff based on information in the consumer report.

In response, plaintiff filed a class action lawsuit against the supermarket, alleging, among other things, that Fred Meyer willfully violated the FCRA by providing an unclear disclosure form that contained extraneous information.

The FCRA Disclosure Requirement

As mentioned above, in Gilberg, the Ninth Circuit held that the FCRA mandates that the disclosure form may contain nothing more than the disclosure itself and cannot contain any extraneous information. However, the FCRA does not define what disclosure means and what information is considered part of the disclosure.

The Fred Meyer Disclosure

The Ninth Circuit Court analyzed the text of the disclosure the plaintiff received. The plaintiff argued that the first paragraph of the disclosure violated the standalone requirement of the FCRA because it mentioned investigative reports, in addition to consumer reports. On this, court ruled that investigative reports are “a subcategory or specific type” of consumer reports and therefore did not violate the FCRA’s standalone disclosure obligation. Also, the first paragraph disclosure explained what “employment purposes” may include and what type of information may be included in the report, which complied with the standard the court just created.

The second and third paragraphs of the disclosure explained what it means to “obtain” a consumer report by providing helpful guidance about what information would be examined to create the report. This language was ruled not to violate the FCRA’s requirement that the disclosure consist solely of a “disclosure . . . that a consumer report will be obtained for employment purposes.”

However, the fourth and fifth paragraphs of the disclosure provided information about an applicant’s rights to obtain and inspect information about the investigation of the applicant. The court stated that this information could pull an applicant’s attention away from the privacy rights protected by the FCRA. The court held that even though Fred Meyer’s included this information in good faith, the fourth and fifth paragraphs of the disclosure violated the standalone disclosure requirement.

“Concise Explanation”

In Fred Meyer, the court held that in addition to a plain statement disclosing “that a consumer report may be obtained for employment purposes,” an FCRA disclosure may also contain “some concise explanation of what that phrase means.” The Ninth Circuit then provided the following examples of what a concise explanation would be: a brief description of what a consumer report entails, how the report will be obtained, and for which type of employment purposes it may be used.

This “concise explanation” standard provides additional clarity for employers on what can and cannot be included in a disclosure statement.

Conclusion

Employers must carefully consider what information is contained in the FCRA disclosure statements they provide applicants. This includes forms provided to an employer by their background screening company. It is ultimately the employer’s responsibility to ensure that the forms are FCRA compliant.

Considering the Fred Meyer decision, if an employer or its background check company includes extraneous information, even if the information is included to assist the applicant, they risk running afoul of the FCRA. This opens employers up to liability in the FCRA, which may result in actual damages, punitive damages, and/or attorneys’ fees.

While employers may include a concise explanation of what employment purposes the consumer report will be used for, the disclosure still must be a standalone document and cannot contain what the court would define as extraneous information. If you are going to conduct employment background checks, use a trusted company that understands the ins and outs of the FCRA. Failure to follow the requirements can land your organization in legal hot water.

Editor’s Note: TruView uses a best-practices approach to FCRA-required documents, including Summary of Rights under FCRA; Client Certifications; Notice to Users of Consumer Reports; Background Check and Investigative Consumer Report Disclosures; State and Local Notices; and appropriate Authorizations. These documents are reviewed by attorneys with a full and current understanding of the FCRA and associated caselaw. TruView undertakes all appropriate and possible due diligence toward minimizing Client legal exposure to the greatest possible extent. If you have any questions or concerns, do not hesitate to Contact Us!

About the Author

Paul L. Scrom Jr., Esq., is a Partner at Jules Halpern Associates LLC. He devotes his legal practice to representing organizations in all employment law matters. Paul regularly advises Human Resources executives, in-house counsel, management, and business owners on compliance and preventative measures in order to avoid expensive litigation and costly government penalties. His counsel includes issues of employee discipline, terminations, discrimination/harassment, wages and hours, independent contractor classifications, restrictive covenants and social media. He frequently presents on legal and HR topics to business groups, professionals, and clients. Paul received his Juris Doctorate in 2012 from the Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University, which he attended on a full merit scholarship. During law school, Paul was Articles Editor of the Hofstra Labor and Employment Law Journal. Prior to law school, Paul graduated Magna Cum Laude from Binghamton University in 2009 with a B.A. in both Philosophy of Law and History. Paul is admitted to the practice of law in the states of New York, New Jersey and the United States District Court for the Southern and Eastern Districts of New York.