A Social Security Number (SSN) trace is the first step in a trustworthy, professional background screen. The SSN trace is a database report that provides addresses, and possibly aliases and other names, linked to a specific Social Security Number. It provides a roadmap for a comprehensive, accurate background check and, when combined with additional search processes to ascertain critical information about an applicant, it helps ensure that the employer complies with federal employment law.

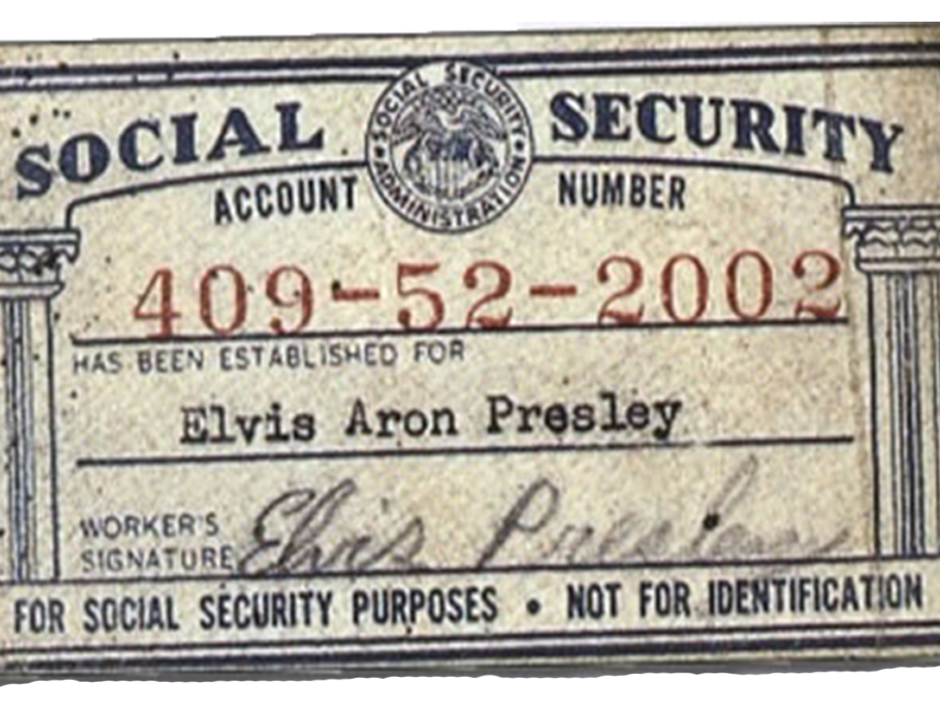

Contrary to common belief, the SSN Trace is not conducted through a federal government database. Rather, data for the SSN trace is compiled from a variety of resources: credit bureaus, third-party resources, applicant change-of-address submissions, magazine subscriptions, customer loyalty programs (such as frequent flier and grocery accounts), telephone directories, online contest entries, and other sources. This data may yield additional names, variations, or aliases; current and previous addresses the subject is presumed to have used over the past seven to 10 years; date or year of birth; possible family associations; phone numbers; and—if the number was issued before June 2011—the state and time frame in which the number was issued. (In June 2011, the Social Security Administration changed the way SSNs are issued to protect integrity and extend the sustainability of the nine-digit numbering system. Called “randomization,” the new method eliminates the significance of the first five digits, which can be used to ascertain where and the time frame in which the SSN was issued.)

From this data, an SSN trace—or SSN “validation,” as it is also called—generates a report listing any addresses, as well as any aliases, linked to the specific SSN provided by the applicant. With a Social Security Number and home addresses, the research analyst can do three important things: first, identify additional information not disclosed by the individual; second, identify in what jurisdictions to perform criminal and civil court searches for any action naming the applicant, potentially uncovering issues relevant to the hiring decision; and third, possibly rule out other information uncovered further in the investigation.

Unfortunately, there is a robust trade in false identifies. Individuals who don’t have the right to work in the U.S. or have unfavorable backgrounds can and do obtain SSNs that belong to other people. An SSN trace alone is usually insufficient to reveal if the SSN belongs to the applicant, unless it returns either no information or information that is completely different from other background information provided by the applicant. Either result is an immediate red flag. If an SSN trace reveals residences different from those provided by the applicant, the research analyst can search the criminal and civil courts in those jurisdictions for any action naming the applicant, potentially uncovering issues relevant to the hiring decision.

To help determine if an applicant-provided SSN is not tied to that individual, a background screener can conduct what is known as a consent-based SSN verification, or CBSV. During a CBSV, information linked to an SSN in the Social Security Administration’s records is compared to information provided by the applicant—such as date of birth, current address, name, and so forth—to determine if the information matches. A signed form of consent from the applicant is required and can be requested at any time during the hiring process, though it does add to the cost of the screen.

However, a CBSV only confirms that the applicant-provided information is consistent with what the government has on file for the SSN; it does not verify employment eligibility. As an employer, incorrectly assuming that a simple SSN trace is all that’s needed to verify an applicant’s right to work under United States law can lead you to hire an ineligible worker and expose you to civil and criminal penalties.

Online right-to-work verifications are conducted using E-Verify, an electronic system maintained by the federal government. Under the E-Verify system, information from the SSA and the United States Department of Homeland Security is compared to information provided by the applicant on Form I-9. All employers must complete Form I-9 for each new hire, but E-Verify checks are voluntary for most U.S. firms; they are required for federal government contractors and certain businesses in some states. E-Verify checks are performed after an offer of employment has been extended but before the new employee has been working for three business days.

The SSN trace is not a perfect system. For example, the SSN database reports are based on credit headers, so if a person never applied for credit or did not use a particular address for credit purposes, then they may not show up in the trace. Data in the reports are entered by human beings over time, and mistakes are made. There are instances of incorrect or incomplete dates of birth, as many credit applications do not require it and, even when they do, often it isn’t verified or only the year of birth is requested.

But a good research analyst or investigator knows this. And they know the best practice for overcoming these flaws is to use multiple sources to complete the “story.” The SSN trace is—and will remain—the important first step in a thorough background screen.

© 2020 TruView BSI, LLC. No portion of this article may be reproduced, retransmitted, posted, or otherwise used in any manner without the written consent of TruView BSI, LLC.